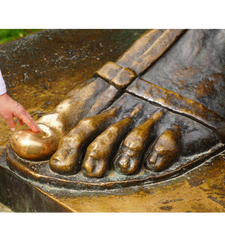

By Tookapic from Pexels on Canva By Tookapic from Pexels on Canva [The following is an excerpted and edited version of a paper written in college. Full circle, I am once again looking at the difference between atonement and apology in my life and found it less painful and more relevant to share publicly some of my story.] Atonement is a loaded word in my family. First, there are religious connotations (e.g., the biblical “atonement day” that my family observed for many years), then there are associations with family failures to resolve conflicts, and if ever discussed together, I imagine there would probably be a philosophical debate of the general definition and atonement’s importance. When I practice atonement, I often picture myself offering an apology in a full bow with my face pressed to the ground, or from head to toe, partially because of a poem on forgiveness I have loved for many years that ends with the line, "to the withered toes." The poem actually envisions a world where we love each other so completely, we need not ever ask forgiveness because from head to withered toe, we are all embraced as belonging. However, for the cycle of leaving the ideal world and getting back to the reality of the life I live now and grew up in, let's look deeper at what atonement really means. After leaving home at 18 and letting go of many of the conservative religious beliefs of my childhood, I dismissed the word “atonement” as an outdated biblical concept that held little value in the complexity and speed of my modern life. As they crudely say, "Don't throw the baby out with the bath water." In the natural maturity that comes with age (and taking classes that prompt introspective reviews), I have had to retrieve and dust off some of these "outdated" concepts and examine them more closely. It turns out that I and those who practice conscious relationship with me are continuously involved in atonement whether we want to recognize it or not. Atonement is more cyclical than linear considering that we will never stop being human, making mistakes, and growing through them to bridge better in relationship with our world. We are all practicing what I might call micro-atonements on some level in relationship because we all experience being the wrongdoer and the victim. In the DOT model, this would be the dance of the Villain and Victim and how they can eventually recognize each other again as the Challenger and Creator. When harm or a rupture in relationship has occurred, moving forward in a healthy way requires some type of atonement (recognition of wrong, apology, and efforts made to make amends). Below I look at my own life with my father and a not yet begun atonement process. Here's a weird coincidence on livestock metaphors and biblical concepts. In the last book of the Bible, the sheep and goats are sorted to determine who goes to hell and who goes to heaven. The hoofed creatures are said to symbolize good people (sheep) and bad people (goats). However, my father could be said to be both a sheep and a goat depending on the perspective or how the story is told. To most people, my father is easily identifiable as the disowned black sheep of my nuclear family. However, my family might take this metaphor and cite a different area of the Bible where God warns about a wolf in sheep clothing. My dad, interestingly, might say he is the scape goat since he identifies as a victim and misunderstood hero. Whatever mammal my father is thought to be, the reality is that he is still human. However, his lack of atonement around his role in the family rupture that led to his exile can make my choice to still be connected to him and in someway forgive him (enough to maintain some type of relationship) suspect to the rest my family who still maintains their no-contact boundary with him almost two decades later. Three atonement and forgiveness theories will be reviewed to highlight the multi-layer dimensions of my father’s lack of atonement (and my forgiving him). Dialectical Theories can explain the cyclical relational aspect of the forgiving process, how the lines between victim and perpetrator can easily get blurred in an ongoing relationship. Next, Uncertainty Management Theories help explain my family’s excommunication of my father, and my own motivation and actions to connect with my father. Finally, the Negotiated Morality Theory towards forgiveness (NMT) can explain what when wrong with my father’s values and how the family relationships with him broke down. Oppression: Abuse, and Neglect My father believes himself to be a community and family “elder” (e.g., his Instant Messenger name is “judge”), which gives him the power to control and demand complete obedience from his family. According to him, he received this role directly from God, and speaks on behalf of God to the people in his world who cannot communicate directly with God (e.g., women, sinners, etc.). Growing up in a family with the “head” member holding this explicit belief about himself, and his right to completely shape and control all aspects of the family life, led to some extremely tragic family and personal consequences (rampant physical and emotional abuse and neglect). Over my parents’ 18 years of marriage, my family became increasingly isolated from all aspects of normal society (e.g., my siblings and I were born at home, home- schooled, provided no social security numbers or existing status in society, and taught that the world would imminently end with a high chance that we all would be tortured and die in the process, etc.) In this polarized relationship setting (of absolute interdependency and control), the other side of being a judge only accountable to God is that my father was unable to psychologically endure and sustain the level of control (or oppression) he believed his family needed, and would cope with his fatigue by "having business to take care of" and disappearing for days and weeks at a time. While we were all palpably relieved in his absence, the paradoxical lack of structure and control left my emotionally battered and co-dependent mother exhausted and depressed, dropping many of our routines (e.g., personal hygiene, education, etc.) and retreating to her spiritual studies or practical wage earning needs. This chaotic polarity cycle resulted in my three siblings and I acting out and turning on each other and ourselves (e.g., including sexual, emotional, and physical abuse). You probably can picture a pretty stressed out life for 4 kiddos growing up. Conversely, there were beautiful escapes where my mother, her sister, and their parents would take us on many types of exploratory outings into the heathen world where we went to botanical gardens, classical concerts, and art galleries. Every so often, more child appropriate activities like water or roller coaster parks were included in our adventures. Imagine the paradox of believing that one will be persecuted to the point of death any day by the people floating down a water ride in giant inner tubes along side you, it is easy to see how these infrequent adventures held their own kind of confusion and stress. Eventually, my mother’s family had enough and threatened to disown my mother and cut off all financial and housing support. Within a year of drama and dread, my mother obtained both a protective and restraining order against my father and then eventually divorced him. My father cried “foul” throughout the entire process, professing his innocence and believing that my mother’s family ( and then later when I reconnected with him, he changed this belief to focus on me as the behind the scene villain who) had turned his wife and children against him. I was 12 years-old when the final divorce decree arrived, and can remember feeling hope about my future for the first time. After what felt like several years of holding my breath and hoping my mother wouldn't wake up one day and get back together with him, my father seemed to accept his banishment and move on. In decreasing frequency, the random hang-up phone calls and the occasional threatening letter/email my father sent citing God’s punishment of unrepentant wives and children stopped coming. Eventually, there was no communication or interaction between my father and my family, which remains largely still true almost 25 years later. Seventeen years ago I decided to reconnect with my father rather than be haunted by such unpleasant memories. I did not fully understand my motivation, except that I needed to have a relationship with him (and then probably end it) as an adult. The complete cut-off from him (even after all he had done) as a child felt unhealthy and unnatural, and I knew that I needed to establish my own boundaries as an adult with him. Since that first phone call, we have met in person three times, and for about 10 years fell into a routine of talking on the phone about once a month. Most topics (e.g., how the rest of the family is doing, anything to do with the past, etc.) remain off limits and our conversations are polite at best. Even though there has been increasing periods of silence, mostly by me over the years, I have had a relationship with my father that has proven surprisingly useful at times, even if just in reminding me of the extremes and how I do not want to be in the world. However, almost two decades later, the time we have spent has not led us much closer in the forgiveness and relational process. In my father's eyes, the whole family history and banishment is one big misunderstanding and persecution. “Atonement involves four components--repentance, apology, reparation, and ....penance.” (Swinburne, 1989) When this paper was originally written 10 years ago, my father had not yet acknowledged or admitted any culpability for the abuses and neglect my siblings and I suffered as a child under his guardianship. A few years ago however, when I decided to try a different route at the end of one of his 45 minute rants connecting me as the source to his loss of family and status as an elder, and I decided to express empathy for the suffering he had experienced and offer my apology for his experienced story, my father almost nonchalantly replied, "well, it was my fault too." This was one of the most jaw dropping moments I have ever experienced in our connection and solidified the model I teach at a whole new level (Guilt + Sadness/Anger = Shame, when I admitted sadness for his perceived victim story my father's sense of shame lifted for a moment and he was able to rise to guilt and say that he had messed up!). I still believe that my father's atonement process has not yet really begun because he did not technically express remorse for how his actions had affected me. Notwithstanding, as one of the victims in this story due to the fact that he was the adult and one of my primary caregivers, I still have the opportunity to heal myself and prepare for my father’s atonement if it should ever manifest in our relationship. Atonement Theories Setting boundaries with my father has been empowering for me as an individual, but it has also created tension and discord in every interaction. Dialectical Behavioral Theory (Waldron & Kelley, 2008) explains the contradiction I have experienced in the identity my father holds as a judge who mandates complete interdependence in all relationships and the valued identity I hold around autonomy and healthy relationship boundaries. “Contradiction emerges from the merging of two or more individual identities and the inevitable co-occurrence of relational phenomena that are opposites, such as... interdependence/autonomy...” (Waldron & Kelly, 2008) My father sees my identification with autonomy as rebellion and brokenness, and I see his belief that “boundaries are bad” and co-dependent ideals as pathological and abusive to impose in any relationship, especially that of a parent and child. The continual contradiction of these core identities between us starts to explain the ongoing dissonance in our connection and the decreasing frequency in contact over time. I have never confronted my father on the ways he hurt me or our family because I believe that he is so wrapped up in his own world it would be pointless to try and talk about it. When he brings up the past, he talks about how he has been victimized by me, the family, and society as a whole. He justifies all of his actions as sourcing from biblical or prophetic teachings of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. If he recites or “claims” a passage from these writings that is at all related to the issue being discussed, he believes he is home free. The action is validated and no more discussion is needed. In Expressing Forgiveness and Repentance, Exline & Baumeister (2000) list “disagreeing with the charge” as a common barrier for a perpetrator expressing repentance. My mother’s divorce was legally granted under irreconcilable differences, but in my father’s eyes, the only difference to reconcile was that we weren’t obedient or submissive enough. What I consider abusive (e.g., no medical intervention for chronic and severe asthma attacks for over 7 years growing up), my father considers protective care and principled boundaries ( e.g., “ 1) There is no cure for asthma, and the drugs just mask the symptoms! 2) The Seventh-Day Adventist prophet says drugs are evil. 3) Your mother undermined me by allowing you to sample your grandmother’s asthma drugs!”). Exlin & Baumeister (2000) continue, “They are likely to focus on their victim status while overlooking their roles as perpetrators.” One of the contradictions for a forgiver in Dialectical Behavior Theory is Mercy versus Justice. (Waldron & Kelley, 2008) If my desire was punishment, Plato argues that the way a wrongdoer suffers the most is by escaping punishment and living with the guilt of their actions (Plato, 1995). Even though my father is not asking for mercy, the question of appropriate punishment should be considered. Kant (1995) theorizes that a criminal cannot comprehend or agree to their punishment because they do not have the autonomy over their life to give it a price or judge the true or right consequence to match their crime. In the abuse of my father isolating me from medical help during my asthma attacks, an equal 7+ years of partial suffocation seems the only logical and equitable justice. Obviously, this is not possible or enforceable. Kant (1995) continues to examine the grey area of crimes for which an equal punishment cannot be equitably revenged such as rape or bestiality. In the 1970’s rapists were castrated, and criminals convicted of bestiality were excommunicated (Kant, 1995). In the case of my father, and his abusive life choices imposed on my family and I, excommunication from our lives makes sense. But then, why would I (the one who might have the most against him) be the one out of five nuclear family members to reconnect? Uncertainty Management Frameworks might explain. The Uncertainty Management Framework’s Information Management Process starts when the uncertainty in a relationship becomes noticeable to one of the individuals (Waldron & Kelly, 2008). There is an uncomfortable discrepancy in the information one has about the relationship (e.g., my family could not maintain healthy boundaries with my father and stay connected, but maybe as an adult I can?), which then goes through an interpretation, evaluation, and decision phase. “... “[F]orgiveness” emerged in participant reports as one means of managing the uncertainty with broken relationships.” (Waldron & Kelly, 2008) Looking back on my decision to reconnect with my father, I see that this uncertainty about the information I remembered from my childhood regarding the safety and issues of being in relationship with my father (e.g., was he really that much of a monster deserving absolute cutoff?) grew as I developed into an autonomous adult. Being connected with my father over the years has been a way that I continually test myself. I've called him my greatest teacher before because of the emotional and cognitive gym I go through whenever we talk. I use my mistakes in not setting boundaries quick enough with him (e.g., recently I listened to him talk for 10 minutes about the world ending and how I would need his guidance to stay alive before I finally cut him off) to grow in the rest of my life and create cleaner boundaries with my family-of-choice relationships (e.g., “I need to go now.”). However, beyond establishing healthy boundaries with an unhealthy family member, can I go one step farther and forgive my father for his wrongs against me? Negotiated Morality Theory (NMT) of forgiveness highlights the moral functions of forgiveness negotiations. The NMT was created to address the complexities and motivations behind the forgiveness process not counted in the previously mentioned theories (Waldron & Kelly, 2008).

One of the core assumptions of NMT is that the tapestry of implicit and explicit values in which relationships are practiced come from ones’ community, personal, and relationship identity (Waldron & Kelly, 2008). My father’s entire value system sources from his “personal relationship with God” and the religious writings he believes to be directly from God. In the process of relying on these teachings (and his generous interpretation of their meanings), my father was excommunicated from his church (many years before I was born). Somewhere along the lines his community values fell apart (or he might say "became uncompromising") and he decided that increasing circles of humans were corrupt and “evil.” Eventually, his relational values (e.g., fidelity, commitment, accountability) fell by the wayside as he became more and more isolated from a community support system. No accountability on the outside led to his polarized behavior of extreme beliefs and control of my family leading to his cycle of fatigue and disappearing for days at a time. Additionally he became less and less able to hold any type of job, and ostracized all outer level family members (e.g., grandparents, in-laws) who were increasingly concerned and trying to support us. A second core assumption of NMT is “values that are socially sanctioned, individually internalized, and relationally shared are most motivating of forgiving and unforgiving behavior.” (Waldron & Kelly, 2008) My father’s relational and community values devolved and his personal values did not transfer individually to our family the way he might have wished. When my mother’s core value of family connectedness was threatened, (e.g., my grandfather offered housing and to pay for a divorce lawyer OR disownment), my mother felt she had no choice but to break off the dysfunctional relationship to my father and choose a system that would support her in raising her children in a financially and physically secure environment (another personal, community, and relational value). My Forgiveness In many of the articles and books I have read on atonement, forgiveness is the last step offered by the victim when the perpetrator has made efforts to atone (Brooks, 2004; Swineburne, 1989; Waldron, 2008). With my father, because he has made no admittance, apology, or retributive actions, in this logic, forgiveness seems premature at best. However, I believe forgiveness is not only about the offending relationship, it is also first and foremost about personal healing and wholeness. Exline & Baumeister (2000) list “reduced guilt and increased confidence based on constructive action” and “mental and physical health benefits...” as two possibilities. Furthermore, NMT mentions four moral functions of forgiveness that seem applicable to my process: Hope: (re)imagining a moral future, Honoring the Self, Redirecting Hostility, and Increasing Safety and Certainty (Waldron & Kelly, 2008). Whether my father ever recognizes the significance of his role and actions within the abusive family atmosphere of my childhood and the dissolution of our family unit, I must move forward in my life--imagining a moral future with healthy relationships that negotiate between the identity needs of interdependence and autonomy. By choosing forgiveness (but not forgetting), I honor myself and my present day adult choices to set boundaries in my relationships that will preserve and protect them from becoming manipulatively abusive. I choose to redirect my anger and hostility from the suffering I experienced through my childhood towards constructive outlets (e.g., most recently getting a doctorate in psychology and educating many on the polarities of human relationship) which allow me to continue to rework the least helpful implicit and explicit relational values my father taught me. Finally, in choosing the forgiving process, I increase my experience of safety and certainty in my interpersonal relationships by consciously practicing the steps in the Uncertainty Management Theories; interpreting my uncertainty, evaluating my options for relieving it, and deciding the healthiest way to get my needs met. “Ultimately, forgiveness makes it possible for wounded people to imagine a future in which their individual dignity is honored and relational justice prevails....” (Waldron & Kelly, 2008) Conclusion Above was an exploration on the atonement process (or lack thereof) of my father for the abuse and neglect of relational power he imposed on myself and my family throughout much of my childhood. The theories reviewed were Dialectical, Uncertainty Management, and Negotiated Morality. If this wasn't long enough, I could also have examined my role as a perpetrator of racial oppression using the Atonement Model by Roy Brooks (2004). It would be interesting to contrast my internalized oppression to my externalized civic complacency and participation in the economic and social-political oppression of black Americans by white Americans. Racial oppression is a continual hot topic for me and I am always re-examining my personal compensatory and rehabilitative actions towards slavery redress. [Maybe this will be the topic for part 2 of my atonement paper re-write.] A further criticism of this reflection would be the simplistic framing of my father as the one responsible for my childhood wounds. On all relationship levels, there were failures by many adults to intervene and meaningfully interrupt the neglect and abuse my siblings and I suffered. For example, my mothers family and friends called Child Protective Services several times, but both of my parents refused to cooperate with the investigation at every step, and CPS did not follow through. One of the criticisms and suggestions for future research for all the reviewed theories above was the limited scope of only dyadic relationship studies (In other words, few studies examined more than two individuals participating in the relational forgiveness process). With better and more comprehensive research, examining the interplay of responsibility and power in my family and the surrounding systems which failed my siblings and I could shed light on how I could change and maintain healthier relationship circles in my adult life moving forward. To conclude on a hopeful note, around the time this original reflection was written, my mother started to recognize how her unaddressed co-dependency led her to become a submissive participant in my father’s abusive behaviors (and therefore in her own way of neglecting to protect her children, also made her an abuser). My mother started a co-dependency recovery group with other women in her church and seemed to begin waking up to some of how she contributed to the mess of a life I grew up in. I do have hope that forgiveness and atonement will develop in some form for all of my family members as we continue to heal and grow. In the meantime however, distance becomes its own kind of boundary as my self-growth and personal development has exponentially propelled me into a fulfilling and demanding career as a therapist and organizational consultant. The following poem summarizes my deepest wish around forgiveness in my life and whatever lies after this one. A Turn to the Right/A Little White Light by Carolyn Reynolds Miller Let there be a season when no one rakes, when all that has ever fallen can drift with ordinary wings. Mithras, I hear you out in the open, humming our favorite tune through a leaf and a comb. Lead us as if we were righteous into the blue light of heaven when no one will forgive anyone just in case it’s condescending, and we will love each other to the withered toes. References

Brooks R. L. (2004). The atonement model. In Atonement and forgiveness: a new model for Black reparations (pp. 141-179). Berkeley: University of California. Dickey, W. J. (1998). Forgiveness and crime: the possibilities of restorative justice. In R. D. Enright& J. North (Eds.), Exploring forgiveness (pp. 106-120). Madison, WS: University of Wisconsin. Exline, J. J. & Baumeister R. F. (2000). Expressing forgiveness and repentance. In M. E. McCullough, K. I. Pargament, & C. E. Thoresen (Eds.), Forgiveness: theory, research, and practice (pp. 133-155). New York: Guilford. Kant, I. (1995). On the right to punish and to grant clemency. In J. G. Murphy (Ed.), Punishment and rehabilitation (pp. 14-20). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Plato (1995). Punishment as healing for the Soul. In J. G. Murphy (Ed.), Punishment and rehabilitation (pp. 8-13). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Photo: Diaz, Ruth 2010. Multimedia digital overlay. Swinburne, R. (1989). Guilt, atonement, and forgiveness. In Responsibility and atonement (pp. 73-92). Oxford: Clarendon. Waldron, V. R. & Kelley, D. L. (2008). Theorizing forgiveness. In Communicating forgiveness (pp. 55-89). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

1 Comment

Josie

6/12/2021 08:07:25 pm

Profoundly resonant in a uniquely thoughtful way. Found this b/c this poem runs through my head like a prayer… though conventionally religious people tend to HATE when I call it a prayer 😄

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author

Ruth Diaz is an organizational consultant and leadership coach on connecting relationships with ourselves and each other at every level. She currently works in Portland, Oregon. Archives

July 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed